The Most Used Marketing Theories in 2024

Marketing Theories is a somewhat complicated name to use in such a general and broad way.

However, at the same time, this is the best way to describe these theories—if we go too far into specifics, they turn into methodologies.

Is there a difference between marketing methodologies and theories? In a way, yes, but in theory 😅.

In practice, marketing theories quickly turn into marketing methodologies, mainly because we are talking about market and business practices.

Due to these characteristics, marketing theories are quickly put to the test and develop into a set of techniques that we understand as methodology.

And often, these marketing theories arise after everything has been tested and applied. This is how the main ones were discovered, by the way.

Someone does something different, sees it working, formalizes it with data and references, and voilà: a new marketing theory is born.

But this is all just for clarification. In this article, we will take a journey through the main marketing theories being applied today.

We will discuss their requirements and their main results. All you need to do is keep reading.

What are the most used marketing theories in 2024?

Before moving on to the longer list, we need to talk about the main marketing theories in use today, in 2024.

Here, we will mainly discuss the marketing theories that are in their golden age, known to everyone in the field.

The main ones we will cover here are the following:

- Inbound Marketing;

- Outbound Marketing;

- The Marketing Mix;

- The Buyer’s Journey;

- Content Marketing;

- The Long Tail.

These six are the main marketing theories being applied today. All of them, however, are informed by other, older, and more complex theories that we will look at more closely in the next section.

Ready to dive into the main marketing theories of 2024?

Inbound Marketing

The first marketing theory we need to mention is Inbound Marketing. It’s so popular that you probably already know by heart what it represents.

Inbound Marketing emerged as a marketing theory in 2005, with Brian Halligan, CEO of HubSpot.

At the time, the theory was built with a strong commercial appeal: HubSpot was in its early stages, and its product—a marketing platform—hadn’t yet gained much traction in the market.

Coining the term, then, was in a way a demand generation strategy. Doing Inbound Marketing is easier if you use a marketing platform, which HubSpot sold.

However, Inbound Marketing exploded in popularity throughout the second decade of the 2000s as the market realized it was more than just a demand generation strategy.

The fact is, Inbound Marketing works very well for Digital Marketing. Its main proposal is that people should seek out your brand, not the other way around.

Potential customers are people, and people have questions. Inbound Marketing, along with other theories, seeks to fill the gaps where people will search for their answers.

This includes Google, Social Media, YouTube, even email. Wherever people search, Inbound Marketing positions itself to provide the answer.

We have an article that dives much deeper into Inbound Marketing. You can access it below.

➡️ Inbound leads: complete guide from generation to sale

The other marketing theories we will analyze here are also part of Inbound Marketing, except for the next one, which is its complete opposite:

Outbound Marketing

At the same time, Inbound Marketing is not the only digital marketing strategy that delivers good results.

Outbound Marketing also offers possibilities in this space, mainly through paid media, such as Google Ads and Social Ads.

Outbound is the complete opposite of Inbound. Here, it’s the brand that goes after its potential customers, not the other way around.

Basically, Outbound’s job is to create ads that will be delivered to the right people at the right time.

But beyond digital ads, any interruptive advertising effort can also be characterized as Outbound Marketing.

The most common, and best examples, are the following:

- Flyers;

- Events;

- Billboards;

- TV and Radio Commercials;

- Sending direct communications to a lead list;

- Telemarketing (in the cold calling modality);

There’s nothing wrong with doing Outbound Marketing. In fact, it’s a fundamental part of the strategies of thousands of brands.

Today, paid media is the most used Outbound Marketing strategy in the world. Its costs are quite reduced, and its work is highly measurable.

It doesn’t make sense to spend R$ 1,000.00 on printing flyers that you don’t even know will yield results.

With the same R$ 1,000 on a Google Ads campaign, you can run several campaigns with audience segmentation and only pay for clicks.

The Marketing Mix

This is one of the most widely used formal marketing theories worldwide, and also one of the oldest.

It was coined in 1960 by Jerome McCarthy in his book Basic Marketing: a Managerial Approach.

It was later expanded in Philip Kotler’s marketing anthology, becoming popularized with the release of the book Marketing Management in 1967.

Basically, the Marketing Mix determines that products achieve sales success depending on four main factors, known as the 4 Ps:

- Price — all products need to have a value appropriate to their target audience. Important: we are not talking about low prices but appropriate prices. A Rolex costing R$ 200.00 would not be attractive to the brand’s target audience, for example;

- Product — the product must be developed with the target audience’s needs in mind. This is important: the product does not “find” its audience after launch. The audience determines how the product will be;

- Place — this point is related to the market availability of the product being developed. Is the imagined target audience available in the launch region? With the advent of digital marketing, geographical barriers have fallen, but not entirely. Issues like very high shipping costs, delivery delays, etc., are still directly related to this P of the Mix;

- Promotion — products need good marketing strategies to fly off the shelves. If no one knows they exist, no one will buy them.

According to McCarthy and Kotler, these points are fundamental in any marketing effort. They arise spontaneously.

It is the responsibility of brands to work on them, but not to create them—that’s how the market works.

With time and the advent of digital marketing, these 4 Ps were expanded, gaining three more:

- People: in the 4 Ps, the brand only interacts with the public through its product. Kotler rectified this with the P of People, which deals with customer service and the relationships that brands build with them through their representatives. This relates both to customer service and to advertising itself;

- Perception: another fundamental point that the 4 Ps do not address is people’s opinions about your brand. This is closely related to the buying process, transparency in information, and the overall experience with the brand. This last point is heavily worked on in the Public Relations field;

- Processes: here, we return to the brand’s internal reality. Processes are the way the product is produced, delivered, and how support is offered. But they also relate to other more operational and administrative points. This is by far the most interesting P of all. It addresses marketing, business, and customer experience at the same time!

The Marketing Mix is so popular that it has several adaptations for different types of marketing.

The Purchase Journey and the Customer Journey

The purchase journey is a marketing theory that aims to categorize the stages a person goes through to make a purchase.

These stages are fourfold:

- Awareness: The person begins to recognize that they have a problem that needs solving or develops an interest in something they were previously unaware of. For example, someone looking to invest in a better keyboard for home office work discovers that there are various models with different specifications.

- Interest: In this second phase, the person starts to understand which products are available in the market that can help solve the problem recognized in the previous stage. In the example, they begin to understand the different keyboard specifications available. At this point, the person becomes an “expert” on what they want to buy but is not necessarily looking at prices yet.

- Consideration: Here, in the third phase, the person starts showing interest in specific products and brands. In the example, they begin to understand which brands offer the specifications they need and also start comparing prices.

- Decision: At this stage, the person is already decided on the product they want but needs to choose a brand. Price plays a significant role at this stage, but so does the product itself. In the example, the person already knows exactly which model they need and is just looking for the brand that offers the specifications at a fair price with good delivery conditions or local purchase options.

The interesting thing about this theory is that it has a linear aspect, but it is by no means rigid.

In reality, you will find people in various stages. They might start already at the Consideration stage, for example, if they are already well-versed in the product and market. This is very common in B2B Marketing.

The Purchase Journey is similar. It just has a different approach, looking at this process from the brand’s perspective.

It is often represented by the Marketing and Sales Funnel, which you can follow below:

We also have an article that goes into great detail about the Purchase Journey. You can access it below:

➡️ Purchase Journey: The “Million-Dollar” Secret of Inbound

The Long Tail

The term “long tail” was coined by Chris Anderson in his book of the same name to discuss a very interesting aspect of marketing as a whole: the availability of products and services and their relationship with sales.

In his book, Anderson analyzes various shopping catalogs from the era when deliveries were made by railroad in the U.S., giving more emphasis to Sears.

In this historical analysis, he noticed that Sears received a much higher volume of sales as it began selling more products and variations of those products.

For example, Sears offered a pocket watch costing $1.00. It had, on average, 100 sales of this watch across the entire country each month.

Using this watch as a base, Sears then launched three other models: one at a much lower price, another at a slightly lower price, and another at a higher price.

Sales of the first watch declined, but when adding up all the sales of all the watches, Sears began selling 300 units.

This is the Long Tail: you have a flagship product, but secondary support lines serve to increase sales across the entire category.

This is pure marketing in a business sense. However, the theory can also be applied to another marketing theory: Content Marketing.

Let’s understand this better in the last item of this topic:

Content Marketing

Content Marketing floats between method and theory.

It is a method because content is a fundamental part of Inbound Marketing, being the main way through which people have their questions answered by brands.

But as a theory, Content Marketing is the great revolutionary of marketing in the digital age.

This understanding began a long time ago with the first legends of copywriting. Marketing, they said, does not exist just to sell but also to entertain and inform the public.

Television itself is a form of Content Marketing, especially open television. Entertainment and informative programs are there with one main objective: to get you to watch the commercials.

The theory of Content Marketing determines that people are not interested in marketing. They are interested in the things that interest them.

Therefore, marketing must interest them and be indistinguishable from entertainment.

This theory is still applied today on social media, for example. Brands are rarely trying to sell something there. They use content to have an emotional impact on those who consume it.

The Long Tail is also applied here. Instead of brands being limited to one type of content, one device (like TV or a Smartphone), or one strategy, they seek all possible ways to produce content.

The more content is produced, the greater the chances of impacting people who do not yet know the brand.

It is precisely because of this characteristic that it is so widely employed in Inbound Marketing.

Learn more: AI content creation - how to do it?

Marketing and Business Theories That Never Go Out of Style

What we just saw in the previous topic are the fundamental theories of digital marketing as it is applied today.

But the term “Marketing” itself is related to business. In fact, its definition is that: a business strategy.

In this sense, marketing theories are constantly applied in business.

But at the same time, we understand that many of them are related to acquiring new customers, like Digital Marketing in general.

In this topic, let’s talk more about some marketing strategies that have this strong correlation with business.

We’ll talk about product design, distribution, trade marketing, delivery, etc.

Maslow’s Pyramid

This is not a marketing theory per se: its origins trace back to 20th-century psychology.

However, Maslow’s Pyramid is widely applied in product design, target audience strategies, and even campaign creation.

This is Maslow’s Pyramid. It seeks to determine levels of human need, ranging from the most basic (food and shelter) to the most advanced, related to the individual’s purpose and the achievement of their life as they would like it to be.

As a marketing theory, Maslow’s Pyramid helps determine categories for creating new products within a segment.

For example, a car manufacturer may have products at all levels of the pyramid. Popular cars tend to be built and advertised with price and safety in mind.

At the same time, utility vehicles are in the middle of the pyramid, as they offer the possibility of taking care of the family, for example.

Meanwhile, sports and luxury cars tend to be at the top, serving as tools for individual achievement.

The point is that analyzing Maslow’s Pyramid as a marketing theory requires a deep understanding of the author’s work.

The best way to do this is by reading his book, A Theory of Human Motivation.

With this more in-depth knowledge, you can apply these concepts with more assurance.

Mendelow’s Matrix

Here is a great example of how marketing theories don’t just address communication but also function as business and management theories.

Mendelow’s Matrix establishes a method for evaluating your main clients and stakeholders, categorizing them into four main categories based on their level of influence (or power) over the business:

Stakeholders are people with interests in your business, whether commercial or administrative.

For example: the board of directors, partners, clients, etc.

Thus, the matrix seeks to determine where your focus points should be: clients and stakeholders with high influence over the business and high interest in its success.

Considering clients, these are the ones who depend on your services for their own results—third-party marketing agencies have many clients like this.

These clients are also interested in the continuation of the contract, so they need—in this case—the agency to continue growing.

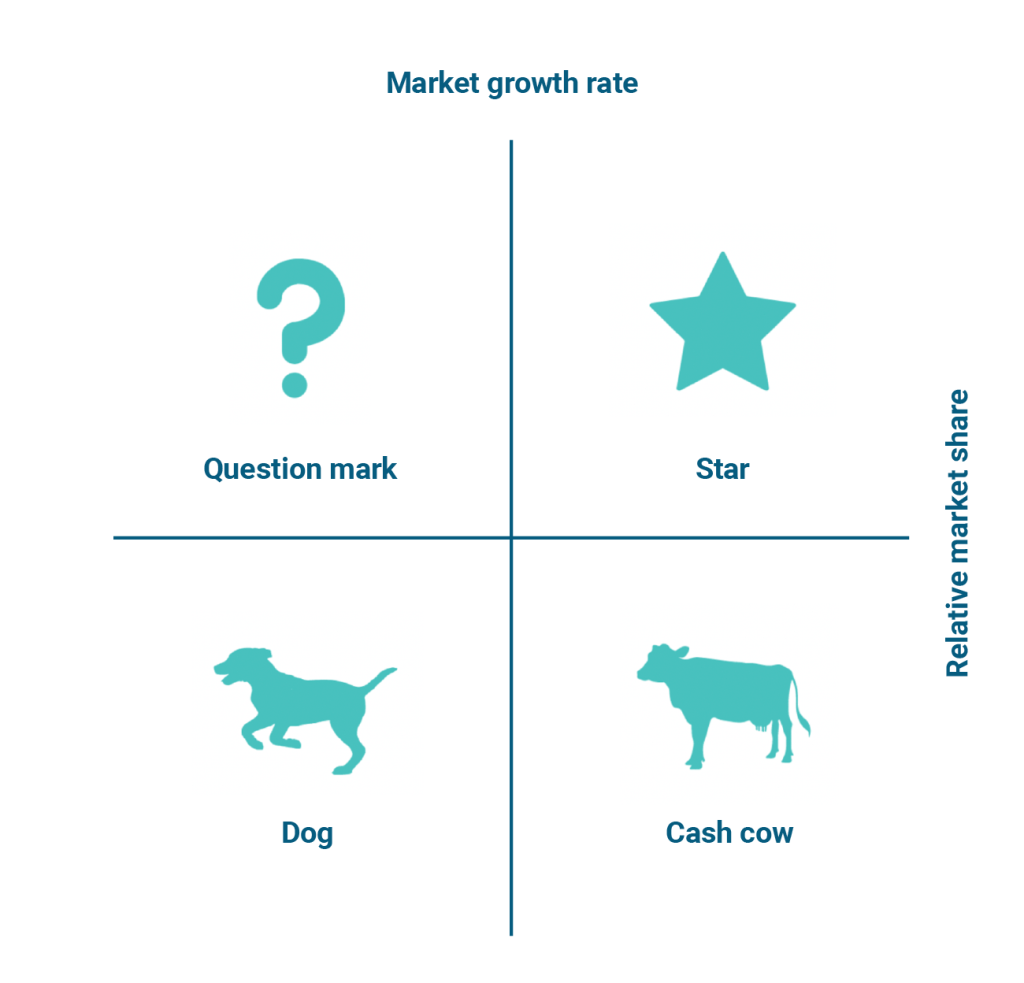

The BCG Matrix

In 1970, Bruce Henderson developed a matrix for the Boston Consulting Group, illustrating how to think about products and where to focus on their development.

Note: He developed the research for BCG to apply to their clients, but it was so insightful that it became one of the leading marketing theories of the 20th century and is still applied daily today.

The BCG Matrix seeks to analyze the importance of a product in terms of the company’s revenue and suggests actions to improve its performance or reduce development costs.

This matrix is mainly applied in Growth Marketing, which requires quick and decisive actions about the future of a product or service.

There are four main categories in this marketing theory:

- Star: High market growth, high market share. This product is growing rapidly and needs investment to become a cash cow in the future, once the initial growth stabilizes.

- Cash Cow: Low market growth but high market share. These are products that consistently generate good revenue for the brand. They are the traditional brands. Here, the philosophy of “don’t fix what isn’t broken” is put into practice. On the downside, cash cows are the products that may suffer from size reductions and even quality cuts since they sell anyway.

- Question Mark: High growth but low market share. These are products that have shown significant growth suddenly, even with low investments. These need close scrutiny, as they could become stars or, in the worst case, dogs.

- Dog: Low growth and low market share. Heavy investments in dogs might turn them into stars by way of question marks, but the risk is high. These products tend to be discontinued.

This is a straightforward way to analyze product distribution, creation, and design.

It’s simple because today, this is evident in any supermarket you enter. By looking at the shelves, you can see all these categories of products, even from the same brands.

A deeper dive into this marketing theory leads to the GE Matrix. More on that below:

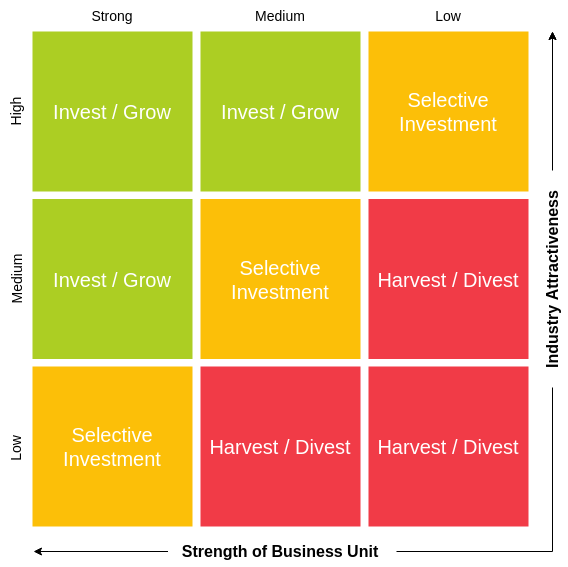

GE-McKinsey Matrix

The issue is that the BCG Matrix primarily addresses fixed products and markets—mainly retail.

It doesn’t address new business units, for example, which have deeper characteristics.

The market share of a business unit might be small, but at the same time, its high ticket value represents a good slice of the revenue. How do you balance the operational costs of these businesses? Is it possible to balance them?

These types of questions aren’t answered by the BCG Matrix. The GE Matrix, developed by McKinsey, provides more room for this.

The Matrix works with three categories of actions:

- Invest;

- Protect (selective gains);

- Exit the investment (and collect dividends);

The higher the industry’s attractiveness and the strength of the business unit within it, the greater the incentives for more aggressive investment.

At the same time, if the strength of the business unit is low (e.g., high costs for little profit) and the industry isn’t very attractive, it’s better to exit the investment and collect what’s possible.

There’s also an action in between these extremes: protect the investment, maintaining it with caution.

When working with this Matrix, you need to add points according to specific characteristics of the business unit and the industry:

- Overall industry attractiveness (market size);

- Competitiveness of the business unit within it (market share);

- PESTEL factors (more on these in the next item);

- Porter’s Five Forces (also more on these below).

Through these scores, you can place the business units in their respective places within the GE Matrix.

The PESTEL Factors

Similar to the S.W.O.T analysis, PESTEL factors aim to analyze the key points of attention when creating a product or defining a target audience.

However, this analysis looks at the external environment—the market itself. It differs from S.W.O.T., which focuses on understanding the company’s structure, an internal effort.

The PESTEL factors are as follows:

- P: Political scenario of a market or region;

- E: Economic scenario, divided into macro (regional) and micro (market);

- S: Social scenario that influences consumer decisions;

- T: Technological scenario in which the brand is inserted;

- E: Ecological scenario of the region;

- L: Legal scenario of the chosen market.

A PESTEL analysis for a legal app, for example, would find limitations in the legal scenario (L) since these platforms have a series of restrictions by the Bar Association.

Similarly, a charcoal industry would face challenges in various scenarios, such as Ecological, Social, and Legal.

These factors alone don’t say much about the viability of a business. But a well-prepared dossier applied to a GE analysis, for instance, can decide the course of a brand for decades.

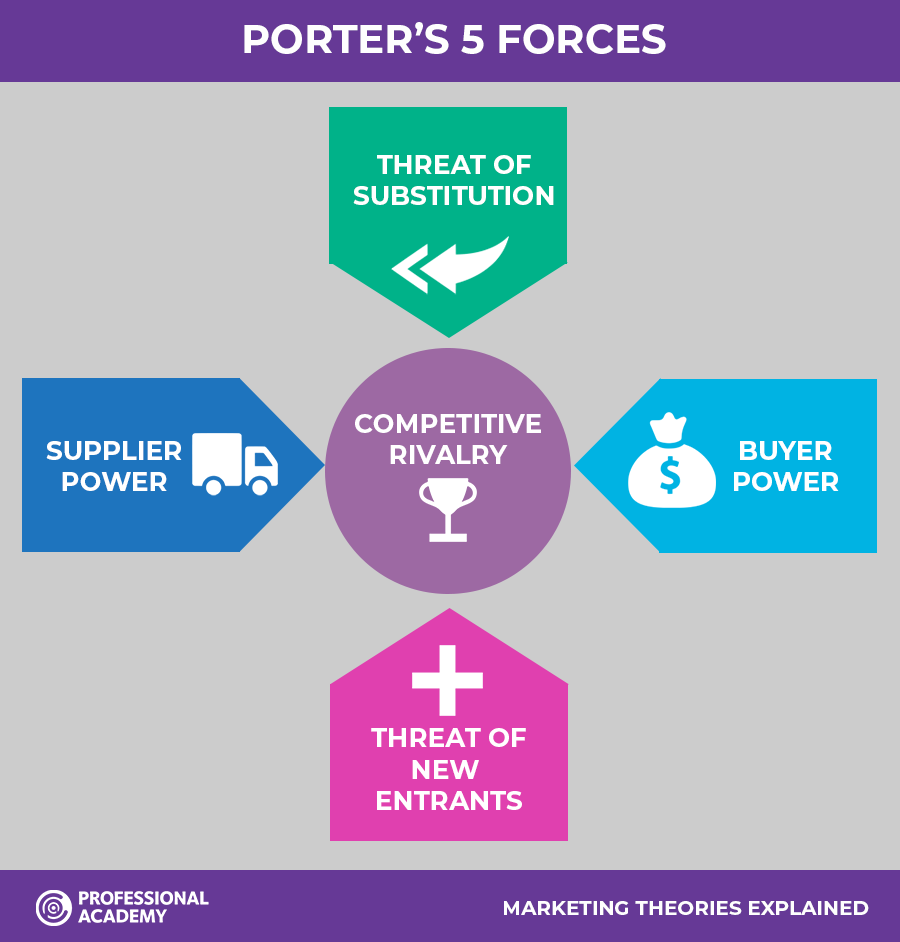

Porter’s Five Forces

Among marketing theories, Porter’s Five Forces are the best for conducting competitor analysis for your product or brand.

These five forces aim to break down the market in which the brand is entering into, well, five forces 😅:

- Competitive Rivalry: How many competitors are there in the market? What is their market share? Questions like these help determine the market in which the brand is entering.

- Threat of New Entrants: This primarily indicates the industry’s attractiveness to new players and relates to the difficulty of starting and operating in it.

- Threat of Substitution: Indicates how likely customers are to switch to another product. Not just another brand but a different product entirely. This is determined by the market’s potential for competitive innovation.

- Bargaining Power of Suppliers: How well can the market sustain the number of players present at the moment and any future expansion? And most importantly, is there enough supply for good raw material purchases?

- Bargaining Power of Buyers: How much can the market bear in terms of prices? It’s crucial to understand the economic scenario in which the brand is entering to avoid increasing the design and manufacturing costs of the products.

These five factors are organized into a simple matrix:

So, did the marketing theories we’ve discussed help you better understand how the world turns? Or did they leave you spinning? 😛

The truth is that most advanced marketing theories are applicable to larger companies, with greater production and needs that small businesses often don’t have.

For small businesses, the focus is on marketing theories related to communication, especially the digital marketing strategies mentioned at the beginning of the article.

By the way, we have an entire article dedicated to marketing strategies for small businesses that’s well worth reading if that’s your case.

Check out our 14 day free trial today – no credi card required!